Coping with Stress using The Stress and Vulnerability Bucket

Stress is a word that consumes our society. We are constantly considering how we are coping with stress. We’re all Human, not Superhero. Even the best Productivity Ninja can have times where the pressure becomes too great. Practical steps learnt from Productivity Training are only employable if we have the headspace to use them. A clever way to consider your stress is using the Stress Vulnerability Bucket (Brabben et al, 2002). It enables us to acknowledge and prioritize stressors. And to consider what coping strategies we have and understand our stress signature.

What is a Stress Bucket?

Giving your mind a high five is important; think of this activity as like going to the gym for your brain!

Grab yourself a pen.

Draw yourself a Stress Bucket;

Stress and Vulnerability Bucket (Brabban and Turkington, 2002)

What is it for?

The stress bucket was primarily a model for identifying and treating relapses of mental illness. It is accepted that we carry genetic and other predispositions to mental illness, but the stress bucket allows us to also consider how life impacts on a person in order to cause mental illness to develop. When our predisposition and stress come together negatively it lessens our resilience or in other words causes our stress bucket to shrink. Our stress signature is a way of identifying when this is starting to happen, if it goes unnoticed this could potentially lead to poor mental health.

Stress is a popular word, however it did not start being used in mental health until 1936, by Hans Selye. If we consider how its been used in other domains, such as engineering it helps us to understand what it means. For example to ‘stress test’ a material is to find out the materials ‘crunch’ point. Similarly stress in humans is the adverse reaction people have to excessive pressures or other types of demand placed on them. The stress bucket enables us to create tools or coping strategies to help us lessen the pressure, much like a Productivity Ninja might!

Coping with Stress

To use the stress bucket the first step requires you to get down on paper your stressors and demands, you can think of these in three levels if its helpful; bottom: those past experiences we have harboured over life that can lower our resilience, or if dealt with, heighten it. In the middle you could consider day to day, month to month stressors and at the top this leaves a small stop gap for anything that might come round the corner.

Understanding what’s in the Bucket

On the left we have our coping strategies, what do we do to make ourselves feel good? Its when we don’t have enough time to engage with these, or perhaps our coping strategies aren’t very healthy that we start to see the stress bucket overflow. Therefore its important to identify what they are and make sure we use them.

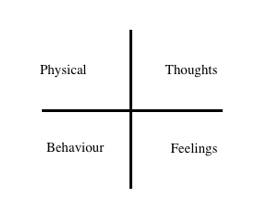

On the right we have our stress signature, our reaction to stress, this takes a level of self awareness to identify and often our loved ones or colleagues might be even better placed to tell us what this is! We can think of the signature as a whole body reaction where by we notice a change in our thoughts, feelings, behaviour and physical self. This reaction is nicely illustrated below in the Hot Cross Bun of CBT (Greenberger & Padesky 1995).

Hot Cross Bun of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Greenberger et al (1995)

Usually we find that our thoughts determine the rest of our hot cross bun reaction, but as we become more overwhelmed the hot cross bun can work in any direction, we may find our new found unhealthy behaviour starts to determine how we feel, for example isolation leading to low mood.

Is Stress Becoming a Problem?

To help us to identify if stress is becoming a problem we should be considering has our negative mood changed to a point where we could say its more severe and has lasted longer than before? Has it started to interfere with, work, relationships and social life?

When considering what sort of coping strategies are useful The Five Ways to Wellbeing (New Economics Foundation (NEF), 2008) is a useful start point. It focuses on connecting, being active, giving, learning and taking notice. Also consider avoiding or reducing caffeine, nicotine and alcohol. Such quick fixes may feel good at the time, but often leave us feeling worse after.

Use the Results

Reach out and utilize what’s available. For example, a Time Management Course takes the pressure off your own mind and might just give you the kick into motivation that you need. Be kind and use realistic self talk, be assertive and learn that its ok to say no!

Zubin and Spring (1977), argued that vulnerability or predisposition is a relatively permanent trait. Therefore utilizing the tools we can take from the stress bucket become even more important in this over stimulated world. Your mind makes you, you so take time out to get to know it and what stresses it.

Author: Rebekah Few, Owner of “Not Lost, but Free”.

Rebekah Few is a freelance mental health and public health consultant and facilitator with a portfolio in health improvement resulting from experience within many facets of the specialty. Rebekah holds an M.Sc. in Health and Social Care Leadership and B.Sc. in Psychology and Philosophy.

She is currently involved in several public health and wellbeing projects. She also provides academic support, including lecturing to a variety of higher education institutions. In addition to this, she runs her own business and blog (Not Lost, but Free) providing bespoke training on all things mental health and wellbeing.

Brabban, A. & Turkington, D. (2002) The Search for Meaning: detecting congruence between life events, underlying schema and psychotic symptoms. In A.P. Morrison (Ed) A Casebook of Cognitive Therapy for Psychosis (Chap 5, p59-75). New York: Brunner-Routledge

Greenberger, D., & Padesky, C. (1995). Mind Over Mood: A Cognitive Therapy Treatment Manual for Clients. New York: Guilford Press

New Economics Foundation (2008) The Five Ways to Wellbeing

Zubin, J., & Spring, B. (1977). Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(2), 103-126